Malcom Gladwell likened memes to genes, but a new study by Facebook shows just how accurate that analogy is. Memes adapt to their surroundings in order to survive, just like organisms. Post a liberal meme saying no one should die for lack of healthcare, and conservatives will mutate it to say no one should die because Obamacare rations their healthcare. And nerds will make it about Star Wars.

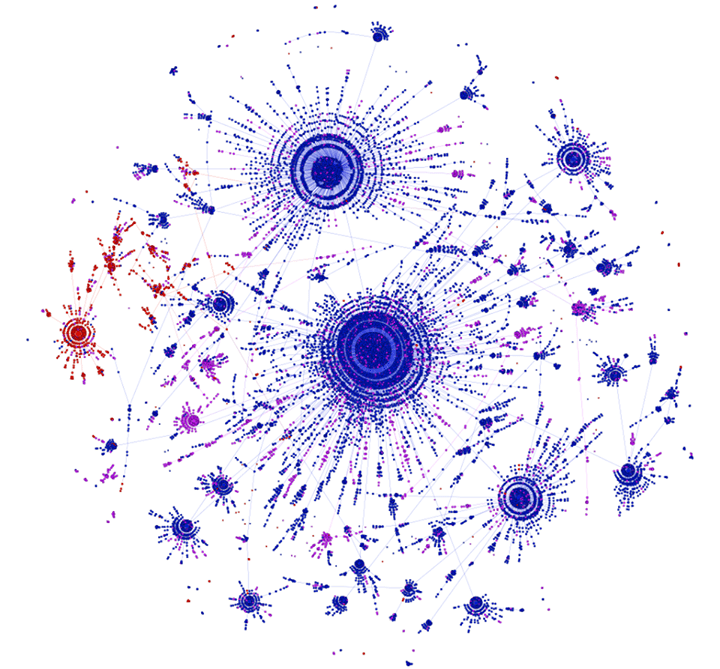

Facebook’s data scientists used anonymized data to determine that “Just as certain genetic mutations can be advantageous in specific environments, meme mutations can be propagated differentially if the variant matches the subpopulation’s beliefs or culture.”

Take this meme:

“No one should die because they cannot afford health care, and no one should go broke because they get sick. If you agree, post this as your status for the rest of the day”.

In September 2009, 470,000 Facebook users posted this exact phrase as a status update. But a total of 1.14 million status updates containing 121,605 variants of the meme were spawned, such as “No one should be frozen in carbonite because they can’t pay Jabba The Hut”. Why? Because humans help bend memes to better fit their audience.

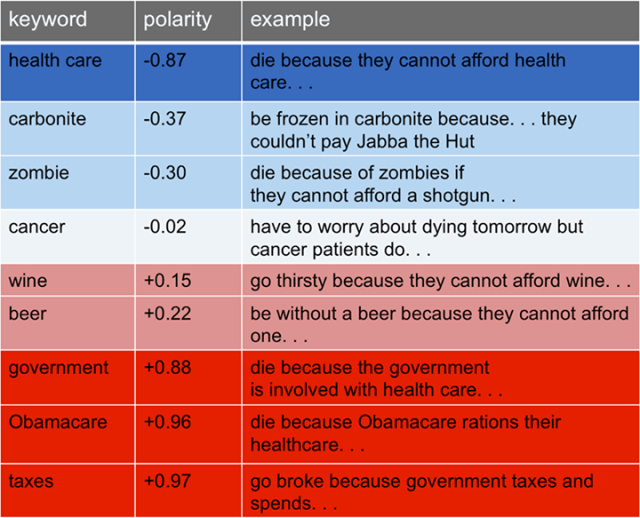

In the chart below you can see how people of different political leanings adapted the meme to fit their own views, and likely the views of people they’re friends with. As Facebook’s data scientists explain, “the original variant in support of Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare) was propagated primarily by liberals, while those mentioning government and taxes slanted conservative. Sci-fi variants were slightly liberal, alcohol-related ones slightly conservative”.

Average political bias (-2 being very liberal, +2 being very conservative) of users reposting different variants of the “no one should” meme.

As I wrote in my Stanford Cybersociology Master’s program research paper, memes are more shareable if they’re easy to remix. When a meme has a clear template with substitutable variables, people recognize how to put their own spin on it. They’re then more likely to share their own modified creations, which drives awareness of the original. When I recognized this back in 2009, I based my research on Lolcats and Soulja Boy, but more recently The Harlem Shake meme proved me right.

Facebook’s findings and my own have signficant implications for marketers or anyone looking to make a message go viral. Once you know memes are naturally inclined to mutate, and that these mutations increase sharing, you can try to purposefully structure your message in a remixable way. By creating and seeding a few variants of your own, you can crystallize how the template works and encourage your audience to make their own remixes.

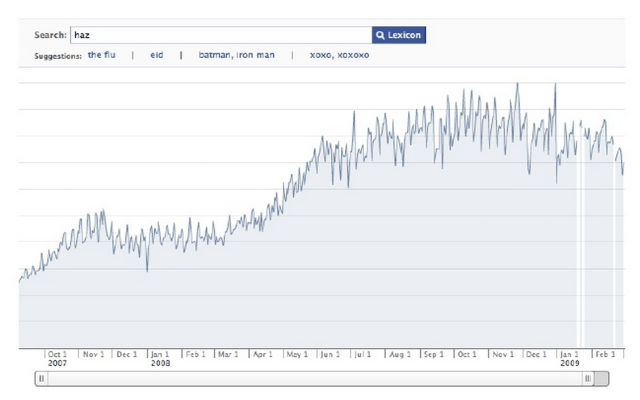

As you can see in this graph from my research paper, usage of the word “haz” as in the Lolcat phrase “I can haz cheezburger” grew increasingly popular for several years. Meanwhile, less remixable memes often only create a spike in mentions for a few days. I posit that high remixability — or adaptability — keeps memes popular for a much longer period of time.

Rise in mentions of the word “haz” in Facebook wall posts, indicating sustained popularity of the highly remixable Lolcats memes – as shown on the now defunct Facebook Lexicon tool

For social networks like Facebook, understanding how memes evolve could make sure we continue to see fresh content. Rather than showing us the exact copies of a meme over and over again in the News Feed, Facebook’s algorithms could purposefully search for and promote mutated variations.

That way instead of hearing about healthcare over and over, you might see that “No one should twerk just because they can’t avoid hearing Miley Cyrus on the radio. If you agree, sit perfectly still with your tongue safely inside your mouth for the rest of the day.”

For more of my Cybersociology work, check out “The Science Behind Why The Harlem Shake Was So Popular“

ConversionConversion EmoticonEmoticon